I wrote here a while back about how great it was to rediscover vinyl. During the lockdown, as we were 100% remote, I implemented what was called Vinyl Friday for my coworkers. I would find the Amazon Music link to a particular album, as that was the most common streaming service among my coworkers, and post what I had on my turntable. Really old music or obscure warranted a playlist off Spotify or just a buy link.

Then we started going back into the office part time. It’s unlikely we’ll ever go full on-site again. More over, it’s unlikely I’ll ever work fulltime in an office again.

But with a much better speaker system and a new office, one where the turntable rests on a shelf sitting on level carpet instead of the sloping concrete of a 100-year-old basement, I decided recently to restart Vinyl Friday. Here’s what the most recent Vinyl Friday, shared on Twitter and Facebook that day, looked like.

UK – UK. When Robert Fripp called it a Crimson with version 3.0, John Wetton and Bill Bruford went out and found Eddie Jobson to replace Mel Collins and David Cross (Crimson’s sax player and violinist respectively, both doubling on keyboards) with Eddie Jobson and Allan Holdsworth to replace Fripp. The result sounds like a follow up to Crimson’s brilliant coda (for now), Red.

Taken with Fripp’s Exposure, released around the same time, UK could be taken as a continuation of Crimson. Wetton is on his way to building Asia while Fripp is a Bruford, Levin, and Belew shy of Discipline.

Wetton’s voice and songwriting are always brilliant in his 70s work, but Bill Bruford’s manic jazz drumming steals this album.

Jeff Beck – There and Back.

There and Back: A Yardbird’s Tale. OK, I just finished The Hobbit, so forgive the pun.

The tail end to Beck’s fusion era. Some of these hearken back to Wired and Blow by Blow. “Freeway Jam,” his most famous instrumental from the 1970s, would not be out of place here. In its place, the album kicks off with Freeway’s sonic sibling, “Star Cycle.” The other standout on this album is “The Pump,” a trippy five-and-a-half minute excuse for a Beck solo cowritten by Tony Hymas and Simon Phillips, both of whom would give Beck’s later classic, Guitar Shop, its signature sound.

And Beck is the Yardbird with the least baggage. He still spins out original music, is not resting on Led Zep’s laurels like Jimmy Page or in an Old Man Yells at Cloud phase like Clapton. And all due respect to the genius that is Page, Beck is the Yardbirds’ greatest guitar alum.

Chicago IX: Greatest Hits Most greatest hits records are a collection of mismatched songs designed to fill a gap in the release schedule. In the case of Pink Floyd, it’s sometimes an excuse to let Syd Barrett share in his former band’s good fortune. (His estate is not exactly complaining.)

Then we get The Eagles’ Greatest Hits, Vols. I and II, the Beatles’ Red and Blue Albums, Rock and Roll, and Hey, Jude. In fact, I never heard of Bread as a kid until their Best of came out.

Then we have Chicago IX, released in the wake of Terry Kath’s bewildering death by misadventure. It would be followed by the Peter Cetera era, but this album ties Kath’s time up in a nice bow. It opens, as any good Chicago collection should, with the frantic “25 or 6 to 4.” Whoever put this together knew what they were doing by alternating the upbeat songs with slow movers like “Wishing You Were Here,” making it sound like the band recorded this all at once. I have a later copy, and I will never forgive Columbia or CBS for truncating that long percussion lead-out at the end of “Only the Beginning,” appropriately the final song on the album. That lead-out is what makes Chicago IX Chicago XI.

Marillion – Fugazi. The second album by Marillion in their original neo-prog phase.

D-d-d-d-do you realize this world is totally fugazi?

Fish is an angry young man on this, a dark successor to Peter Gabriel and more serious alternative to Phil Collins. If you wonder why I’m making references to Genesis here, listen to this album. Early Genesis served as the template for Marillion’s initial run, though guitarist Steve Rothery is clearly a Pink Floyd fan, putting more Gilmour through his guitar than Gilmour. (Or should I say more Rothery?)

Someone on Twitter commented that this was the weakest album of the Fish era, and knowing the commenter as I do, he’s setting a high bar. I commented that I had no vinyl from the current h era (h being Steve Hogarth, apparently Fish’s favorite Marillion lead singer as h seems to be the only member he talks to semi-regularly.) I asked Facebook Afraid of Sunlight or Happiness Is the Road? And if the vote was for both, I’d have to get Fish’s gut-wrenching masterpiece, Misplaced Childhood. Which is not really a problem, is it?

The James Gang – Miami. Forgive me, father, for I have sinned. I have no James Gang vinyl or CD with Joe Walsh with the James Gang, but I have this obscure Tommy Bolin classic.

A few words about Tommy Bolin. Over the last five years, I have heard or read Brian Wilson, Joe Bonamossa, Mike Love, and Ritchie Blackmore (who apparently was pleased with his replacement in Deep Purple, but not with Purple itself) praise this guitar genius and mourn his passing in 1976. Bolin was all over the map in a band called Zephyr (whose singer most definitely was not the new Janis Joplin!), laying tracks for jazz great Billy Cobham, and, of course, pulling a Steve Morse (another Bolin fan) and refreshing Purple’s sound after Blackmore’s first departure.

After a disastrous album following Joe Walsh’s departure, the James Gang took Walsh’s advice and hired this young Sioux from Iowa. Miami has much in common with Walsh’s version of the band, but this is quintessential Bolin with its sliding notes, sometimes almost sounding like a gospel backup singer. “Red Skies” is done by the band’s lead singer, but “Spanish Lover” is a preview of his solo work to come.

Sadly, Bolin’s habits got the better of him while on tour with Jeff Beck at the end of 1976. Too bad, because he had a brilliant career echoing Beck’s, future Purple guitarist Joe Satriani’s, and Eric Johnson’s, a guitar-only artist. He also would have funded his retirement nicely playing sessions. What a loss.

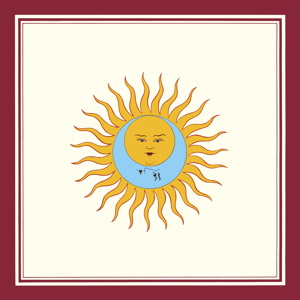

King Crimson – Larks’ Tongues in Aspic. The title track, in two parts, would ultimately take until the mid-2000s to complete. And I suspect there’s more Robert Fripp just can’t be bothered to lay down.

This is the debut of Crimson 3.0. The OG Crimson was an ever-rotating cadre of musicians that included ELP voice and bass player Greg Lake. This era was more about the album (or rather trying to perfect Court of the Crimson King) than who was in the band. In fact, after Court, Fripp offered to quit and let the band do what they wanted. The others said no, they loved what he was doing and left to get out of his way. Version 2.0 was the one-album Islands line-up that turned an unknown singer named Boz Burrell into Bad Company’s bassist. It also demonstrated that Crimson wasn’t so much a rock band as it was a jazz band that made an art of breaking all the rules. Otherwise, how could Fripp justify a final line-up with three drummers?

Version 3.0 is Crimson at its most accessible and coherent. John Wetton comes into his own as a front man and was already an accomplished bass player. Bruford is, as always, brilliant. So brilliant, only he could keep Chester Thompson’s seat warm in Genesis, and only Alan White could replace him in Yes. (As Bruford pointed out, White did it with only three days’ rehearsal. He approved of the result.) David Cross’s violin replaces Mel Collins on sax. (Collins just brought Crimson in for a landing not long ago.) Larks’ Tongues parts 1 and 2 are sonic experiments that are, let’s be honest, acquired tastes, especially Part 1. Part 2 shows Fripp’s interest in heavy metal and punk. But the ballads move Wetton front and center with “Book of Saturdays” and “Exiles.” Then there’s the playful “Easy Money,” a sarcastic take on the music biz that lacks the overt (yet snarky) sexism of the previous album’s “Ladies of the Road.”

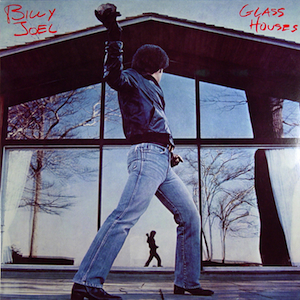

Billy Joel – Glass Houses.

One of the albums my wife bought me with my first turntable (since 1991.) Joel had a three-album salvo that were pure Billy Joel and pure New York: The Stranger, 52nd Street, and this classic.

It opens, appropriately, with that rock Billy Joel is holding on the cover shattering glass and launching into “You May Be Right,” maybe Joel’s most pure rock and roll song to date. Side 1 is all classics and 2/3 rockers: “It’s Only Rock and Roll to Me,” “Big Shot.” “Sometimes a Fantasy.”

This is Billy Joel at his peak. He’d have an angry rant on the world in the brilliant Nylon Curtain (another one I need on vinyl) and what could have been a great coda with An Innocent Man. When we get to The Bridge….

Have I mentioned I love the triple threat of The Stranger, 52nd Street, and Glass Houses?